Nel 2026 l'intelligenza artificiale è entrata a far parte di alcuni degli aspetti più delicati del lavoro quotidiano. Le riunioni che un tempo venivano annotate su quaderni o rimanevano impresse nella memoria ora vengono registrate, trascritte, riassunte e archiviate, spesso in modo automatico, spesso per impostazione predefinita e spesso senza che i team si fermino a riflettere su ciò che questo comporta in termini di privacy. Ecco perché il dibattito sull'intelligenza artificiale e la privacy è diventato così acceso, soprattutto quando si tratta di sistemi di registrazione vocale basati sull'intelligenza artificiale, che si collocano proprio al crocevia tra praticità e rischio.

Passo molto tempo a scrivere su questo argomento, e il copione è sempre lo stesso. I team non sono contrari all'intelligenza artificiale. Sono impegnati, oberati di lavoro e sinceramente grati per gli strumenti che li sollevano dalle mansioni amministrative quotidiane. Allo stesso tempo, però, sono a disagio. Vogliono sapere dove finiscono le loro conversazioni, chi può accedervi, per quanto tempo vengono conservate e se quelle registrazioni vengono riutilizzate in modo discreto in modi che non hanno approvato. Queste preoccupazioni sono ragionevoli.

Qui daremo uno sguardo all'intelligenza artificiale e alla privacy attraverso una lente molto specifica, quella dei dispositivi di registrazione vocale basati sull'intelligenza artificiale nel 2026. Non si tratta di etica astratta e argomenti difficili da vendere. Solo i rischi reali che questi strumenti comportano, come tali rischi si manifestano nella pratica e cosa i team dovrebbero capire prima di premere il tasto di registrazione e affidare le loro conversazioni a un sistema di intelligenza artificiale.

Che tu stia già utilizzando un sistema di presa appunti basato sull'intelligenza artificiale o che tu stia ancora valutando come integrarlo nella tua routine lavorativa quotidiana, questo articolo ti fornirà alcuni spunti concreti da tenere in considerazione quando scegli un sistema di presa appunti basato sull'intelligenza artificiale o decidi di passare a un altro fornitore.

TL;DR

Gli strumenti di presa appunti basati sull'intelligenza artificiale consentono di risparmiare tempo, ma trasformano anche conversazioni informali dal vivo in registrazioni permanenti e ricercabili che comportano rischi reali per la privacy in materia di consenso, attribuzione, conservazione, formazione dei modelli e uso secondario.

I team hanno ragione a chiedersi come vengono archiviate le registrazioni, chi può accedervi, per quanto tempo vengono conservate e se i dati vengono riutilizzati oltre la creazione delle note.

Un'adozione responsabile significa verificare la base giuridica, la minimizzazione, i diritti di cancellazione, le politiche di formazione e le impostazioni predefinite, quindi scegliere fornitori che rendono visibili le registrazioni, limitano l'accesso, documentano chiaramente l'elaborazione e offrono ai team un controllo reale sulla conservazione e la rimozione dei dati.

Cosa rende gli strumenti di presa appunti basati sull'intelligenza artificiale un rischio unico per la privacy

Non tutti gli strumenti di IA comportano lo stesso tipo di esposizione della privacy. Un assistente di progettazione o un modello di analisi dei dati lavora in genere su informazioni che gli utenti scelgono di inserire deliberatamente e spesso dopo un certo livello di revisione. Gli strumenti di IA per la presa di appunti sono diversi. Operano su conversazioni dal vivo, pronunciate in tempo reale, che spesso contengono pensieri non filtrati, contesti sensibili e informazioni che non sono mai state pensate per essere riportate fedelmente.

Questa differenza è importante perché modifica sia la natura dei dati trattati sia le aspettative delle persone in materia di controllo, consenso e utilizzo a valle.

Registrazione di conversazioni dal vivo

Il primo e più evidente cambiamento avviene nel momento in cui una riunione viene registrata. Le conversazioni dal vivo non sono documenti statici. Sono fluide, contestualizzate e spesso esplorative. Le persone parlano in modo diverso quando credono che una conversazione sia temporanea. Speculano, si correggono, mettono alla prova idee e condividono informazioni che potrebbero non mettere mai per iscritto.

Quando un sistema di registrazione basato sull'intelligenza artificiale registra una riunione, trasforma quello scambio transitorio in un artefatto permanente. Ciò crea un rischio per la privacy ancora prima che inizi qualsiasi elaborazione da parte dell'intelligenza artificiale. La registrazione cattura il tono, l'intento, i commenti marginali e i momenti che non avrebbero mai dovuto essere conservati al di fuori della sala. In molte organizzazioni, è qui che inizia il disagio, soprattutto quando le registrazioni avvengono automaticamente o quando i partecipanti non sono pienamente consapevoli di ciò che viene registrato.

Esiste anche un divario di consenso che i team spesso sottovalutano. Nelle riunioni distribuite o interaziendali, non tutti i partecipanti potrebbero appartenere alla stessa organizzazione o operare secondo le stesse politiche. La registrazione di una conversazione dal vivo solleva interrogativi su chi abbia acconsentito alla registrazione, come sia stato ottenuto tale consenso e se esso possa reggere a un esame approfondito in un secondo momento.

Trascrizione e attribuzione dei parlanti

La trascrizione aggiunge un secondo livello di rischio trasformando il parlato in testo. Il linguaggio parlato è disordinato. Comprende interruzioni, sovrapposizioni, false partenze e frasi informali che possono assumere un significato molto diverso una volta trascritte. Una trascrizione congela quei momenti in un modo che può sembrare rivelatore, specialmente quando attribuito a oratori nominati.

L'attribuzione dei relatori aumenta ulteriormente la sensibilità. Identificare chi ha detto cosa crea un registro ricercabile dei contributi, delle opinioni e delle dichiarazioni individuali. Nelle riunioni interne, ciò può influire sulla fiducia, in particolare quando sono coinvolte dinamiche di potere. Nelle riunioni esterne, solleva interrogativi sul fatto che clienti, partner o candidati si aspettino che le loro parole siano attribuite e archiviate in modo permanente.

In questo caso è importante l'accuratezza, ma lo è anche l'interpretazione. Attribuzioni errate, trascrizioni parziali o perdita di contesto possono creare documenti che non riflettono il significato effettivo, ma che continuano a esistere come documenti dall'aspetto autorevole. Dal punto di vista della privacy, si tratta di un rischio per la reputazione e di una questione di equità.

Archiviazione, conservazione e ricercabilità

Una volta registrata e trascritta, una riunione deve essere archiviata da qualche parte. È proprio nell'archiviazione che molte preoccupazioni astratte relative alla privacy diventano concrete. Spesso i team non si rendono conto per quanto tempo vengono conservate le registrazioni, dove sono ospitate o chi può accedervi per impostazione predefinita.

La ricercabilità amplifica questo rischio. La possibilità di cercare dati relativi a riunioni tenutesi nel corso di mesi o anni è molto utile, ma significa anche che informazioni sensibili possono venire alla luce molto tempo dopo che il contesto originale è ormai svanito. Un commento casuale fatto durante una sessione di brainstorming può riemergere durante audit, controversie o revisioni interne, distaccato dalle condizioni in cui è stato pronunciato.

Le politiche di conservazione dei dati sono quindi fondamentali, ma spesso vengono trascurate. La conservazione illimitata sembra conveniente, ma aumenta l'esposizione nel tempo. Più a lungo i dati rimangono disponibili, maggiore è la possibilità che vengano consultati, utilizzati in modo improprio o violati. I team attenti alla privacy chiedono sempre più spesso non solo dove vengono archiviati i dati, ma anche per quanto tempo rimangono lì e con quale facilità possono essere rimossi.

Elaborazione AI, sintesi, punti salienti e azioni da intraprendere

Gli strumenti di presa appunti basati sull'intelligenza artificiale offrono molto più della semplice trascrizione. Riassumono le discussioni, estraggono i punti salienti, generano azioni da intraprendere e talvolta deducono intenzioni o priorità. Questo livello di elaborazione introduce ulteriori considerazioni relative alla privacy.

I riassunti sono interpretazioni. Comprimono conversazioni complesse in narrazioni semplificate, che possono modificare l'enfasi o omettere sfumature. I punti salienti e le azioni da intraprendere spesso mettono in evidenza decisioni o responsabilità che i partecipanti non hanno esplicitamente inquadrato in questo modo. Sebbene utili, questi risultati possono creare registrazioni che sembrano più definitive di quanto non fosse in realtà la conversazione sottostante.

Dal punto di vista della privacy, la preoccupazione non riguarda solo il fatto che l'IA elabori i dati, ma anche il modo in cui tali risultati vengono utilizzati e condivisi. È più probabile che i riassunti vengano inoltrati, archiviati in strumenti di progetto o consultati in un secondo momento, estendendo la portata della conversazione originale oltre il pubblico previsto.

C'è anche la questione dell'accesso al modello. I team vogliono capire se i dati delle riunioni vengono elaborati in ambienti isolati, se vengono conservati dopo l'elaborazione e se vengono mai esposti a sistemi che esulano dal compito immediato di generare note.

Rischio di uso secondario e timori relativi all'addestramento dei modelli

Una delle preoccupazioni più ricorrenti riguardo ai sistemi di registrazione vocale basati sull'intelligenza artificiale è il loro utilizzo secondario. I team temono che le loro conversazioni possano essere riutilizzate per scopi non previsti, come il miglioramento dei modelli, l'addestramento di sistemi futuri o la generazione di approfondimenti che esulano dall'ambito della riunione originale.

Questi timori non sono infondati. Nell'ecosistema più ampio dell'IA, il riutilizzo dei dati è comune e i messaggi dei fornitori sono spesso vaghi. Affermazioni come "non addestriamo i nostri modelli sui vostri dati" possono nascondere dettagli importanti relativi all'elaborazione temporanea, all'anonimizzazione o all'apprendimento aggregato.

Per le organizzazioni attente alla privacy, la questione fondamentale è il controllo. Esse desiderano risposte chiare e verificabili sul fatto che i dati delle riunioni contribuiscano in qualche modo alla formazione dei modelli, sull'esistenza di meccanismi di opt-out e sulle modalità di applicazione di tali impegni dal punto di vista tecnico, non solo contrattuale.

Il rischio di un uso secondario si estende anche internamente. Anche se un fornitore gestisce i dati in modo responsabile, le organizzazioni devono considerare come i dati registrati ed elaborati relativi alle riunioni potrebbero essere riutilizzati dai propri team in modi che i partecipanti non avevano previsto.

Ecco perché chi prende appunti con l'AI si sente diverso

Nel loro insieme, questi fattori spiegano perché gli strumenti di AI per la presa di appunti risultano particolarmente sensibili rispetto ad altri strumenti di AI. Essi operano su comunicazioni umane non protette, creano registrazioni permanenti da scambi temporanei e aggiungono un livello di interpretazione ai dati grezzi.

Il rischio per la privacy non è un comportamento scorretto intrinseco, bensì l'esposizione. Comprendere questa distinzione è il primo passo per valutare questi strumenti in modo responsabile, anziché reagire con un'accettazione indiscriminata o un rifiuto totale.

Le vere preoccupazioni dei team e perché non sono irrazionali

Quando i team esitano nei confronti dei sistemi di presa appunti basati sull'intelligenza artificiale, si è tentati di interpretare tale resistenza come paura del cambiamento. In pratica, le preoccupazioni sollevate dalle persone sono specifiche, situazionali e spesso fondate sull'esperienza diretta. Trascorrendo del tempo nelle comunità di professionisti, gli stessi temi emergono ripetutamente, indipendentemente dal ruolo o dal settore.

Riunioni interne e sicurezza psicologica

Uno dei primi punti di tensione relativi ai dispositivi di registrazione vocale basati sull'intelligenza artificiale emerge durante le riunioni interne, dove la conversazione è esplorativa e spesso incompleta. I team descrivono ripetutamente un cambiamento quando la registrazione entra nella stanza. Le persone rallentano. Il linguaggio diventa più rigoroso. Le idee diventano più sicure prima di diventare migliori.

Questo cambiamento emerge chiaramente in una lunga discussione su Reddit sull'etica degli strumenti di presa appunti basati sull'intelligenza artificiale sul posto di lavoro. Nel thread, l'autore del post originale descrive l'introduzione di uno strumento di presa appunti basato sull'intelligenza artificiale nel proprio team e il disagio suscitato piuttosto che l'interesse. Un collega ha chiesto di essere informato prima di ogni riunione se fosse in corso una registrazione, affermando di non gradire affatto essere registrato, anche se non lo avrebbe impedito attivamente.

Le risposte dimostrano chiaramente che questa reazione è comune. Un commentatore ha scritto: "Chiediamo SEMPRE ai partecipanti se possiamo registrarli prima di qualsiasi riunione. È una questione di professionalità di base". Un altro ha detto: "Se scoprissi che mi hai registrato senza il mio consenso, ti segnalerei alle Risorse Umane. È una grave violazione della privacy".

Ciò che emerge dalla discussione è che pochissime persone si oppongono alla presa di appunti in sé. La preoccupazione riguarda piuttosto la permanenza e la perdita di controllo una volta che il linguaggio parlato viene registrato ed elaborato. Un utente ha spiegato: "Non voglio che le mie parole vengano inserite in un'intelligenza artificiale per produrre un 'riassunto', perché non mi fido della sua capacità di produrne uno accurato". Questo disagio deriva dal rischio che il contesto venga appiattito e l'intento venga frainteso.

Diversi commentatori hanno anche descritto come la registrazione alteri il comportamento del gruppo nel tempo. Le persone hanno affermato di sentirsi a proprio agio una volta annunciata la registrazione, ma si sono fortemente opposte alla registrazione a sorpresa, che molti hanno descritto come disonesta. Altri hanno espresso preoccupazione per il fatto che strumenti di terze parti spostino le conversazioni interne al di fuori dei sistemi approvati, con un commentatore che ha chiesto se qualcuno fosse davvero a proprio agio con il fatto che "tutte le discussioni interne dell'azienda" venissero inviate altrove.

Nel loro insieme, queste risposte indicano lo stesso problema di fondo. La sicurezza psicologica dipende dalla capacità delle persone di esprimere liberamente le proprie opinioni, cambiare posizione e parlare in modo imperfetto. Quando le riunioni vengono regolarmente registrate, trascritte, attribuite e archiviate, tale libertà si riduce. Le conversazioni diventano più caute e meno aperte, il che influenza ciò che viene detto e ciò che non viene mai detto.

I team coinvolti in queste discussioni descrivono un minor numero di idee provvisorie e una partecipazione più cauta una volta che la registrazione diventa routine. Questo cambiamento influisce sul modo in cui vengono esaminati i problemi e su come vengono prese le decisioni, motivo per cui il disagio nei confronti della registrazione interna non può essere liquidato come semplice riluttanza ad adottare nuovi strumenti.

Chiamate dei clienti e fiducia esterna

Le chiamate dei clienti e dei consumatori comportano un tipo di rischio diverso, poiché le persone all'altro capo del telefono sono al di fuori del controllo dell'organizzazione. Non condividono le politiche interne, non hanno accettato le scelte relative agli strumenti interni e spesso introducono informazioni sensibili nella conversazione senza sapere come potrebbero essere gestite.

Questo divario nelle aspettative emerge chiaramente in un'altra discussione su Reddit sul motivo per cui molti professionisti evitano gli strumenti per prendere appunti. Un assistente esecutivo ha descritto uno scenario legale in cui un cliente avrebbe accettato che un collega junior partecipasse a una chiamata, ma avrebbe immediatamente obiettato alla presenza di un sistema di presa appunti basato sull'intelligenza artificiale. La conclusione era semplice. Le persone si sentono più a loro agio a fidarsi di un'altra persona piuttosto che di un sistema automatizzato quando la posta in gioco è personale.

In altri punti del thread, i commentatori hanno descritto organizzazioni che rimuovono o bloccano attivamente i dispositivi di registrazione vocale basati sull'intelligenza artificiale dalle riunioni, sostenendo che le conversazioni riservate spesso sconfinano in territori sensibili senza preavviso.

La preoccupazione in questo caso non è la registrazione in sé, ma la perdita di controllo una volta che la conversazione esce dalla chiamata. I clienti possono aspettarsi che vengano presi appunti, ma raramente si aspettano che le loro parole vengano archiviate, rese ricercabili ed elaborate da un sistema di intelligenza artificiale che altri possono consultare in un secondo momento.

Diversi partecipanti hanno osservato che le conversazioni con i clienti non si limitano strettamente agli argomenti previsti dall'ordine del giorno. Le chiamate di routine possono rapidamente spostarsi su questioni personali, finanziarie o legali, il che rende rischiosa la registrazione indiscriminata.

Per questo motivo, molte organizzazioni adottano un approccio cauto. Alcune limitano l'uso dei dispositivi di registrazione vocale basati sull'intelligenza artificiale all'uso interno. Altre richiedono un'approvazione esplicita per le chiamate esterne. Alcune li evitano del tutto nei contesti di contatto con i clienti, dando priorità alla fiducia rispetto alla comodità.

Ecco perché le chiamate esterne rimangono uno dei contesti più delicati per chi prende appunti con l'AI. Il problema non è il permesso sulla carta. Si tratta piuttosto di capire se lo strumento soddisfa le aspettative delle persone dall'altra parte della linea.

Conversazioni relative alle risorse umane, agli aspetti legali e finanziari

Questo sentimento emerge ripetutamente quando chi lavora con informazioni riservate parla degli strumenti di trascrizione basati sull'intelligenza artificiale. Si tratta di un limite pratico piuttosto che di una posizione filosofica. Nei settori delle risorse umane, legale e finanziario, le riunioni sono già considerate sensibili per definizione e anche le più piccole incertezze comportano rischi enormi.

In questi contesti, le persone sono profondamente consapevoli che le parole non esistono in modo isolato. Il significato dipende dal tono, dal momento in cui viene pronunciata e dall'intenzione, e tutto ciò può andare perso una volta che il discorso viene trasformato in una registrazione permanente. Una conversazione sulle prestazioni, una discussione sulla ridondanza o una sessione di strategia legale cambiano carattere quando diventano ricercabili e revisionabili in un secondo momento da qualcuno che non era presente.

Le preoccupazioni relative al riutilizzo aumentano tale disagio. Gli operatori del settore sottolineano spesso che le politiche sulla privacy possono consentire l'utilizzo di registrazioni audio o trascrizioni per scopi che vanno oltre la creazione di appunti, tra cui la formazione di modelli o la condivisione all'interno di sistemi più ampi. Anche quando tali pratiche vengono rese note, la possibilità di un utilizzo secondario sembra incompatibile con conversazioni che presuppongono una rigorosa riservatezza.

In queste funzioni si riscontra inoltre una forte preferenza per mantenere il controllo a livello locale. L'elaborazione sui dispositivi viene spesso citata come più accettabile rispetto ai caricamenti basati sul cloud, poiché riduce l'incertezza relativa alla destinazione dei dati e a chi potrebbe accedervi in seguito. Tale distinzione è particolarmente importante nei casi in cui il trattamento delle informazioni comporta conseguenze legali, finanziarie o lavorative.

Di conseguenza, i team delle risorse umane, legale e finanziario tendono ad agire in modo conservativo. Si affidano a note manuali. Limitano la registrazione. Evitano strumenti che trasformano discussioni delicate in artefatti di lunga durata. Queste decisioni non riguardano la resistenza al cambiamento. Riflettono la consapevolezza che, una volta che determinate conversazioni vengono registrate ed elaborate, l'esposizione non può essere annullata.

In questi contesti, la moderazione è una risposta razionale al peso che tali conversazioni comportano.

Consenso e fiducia dei dipendenti

Una delle preoccupazioni più accese riguardo ai sistemi di registrazione vocale basati sull'intelligenza artificiale è se i dipendenti abbiano davvero la possibilità di scegliere se essere registrati e trascritti. Sulla carta, le aziende spesso gestiscono la questione con politiche aziendali o notifiche all'interno delle app. Nella pratica, ciò lascia molte persone con la sensazione di avere poco controllo reale su come le loro parole vengono registrate e utilizzate.

I professionisti della privacy e i commentatori hanno segnalato chiaramente questo problema. Alcuni esperti sostengono che gli strumenti di registrazione basati sull'intelligenza artificiale confondono i confini tra la notifica passiva e il consenso attivo e informato, perché spesso i partecipanti scoprono che uno strumento li ha registrati solo a posteriori, quando la registrazione o la trascrizione compare nei loro file o quando si discute della conservazione e del riutilizzo dei dati. Ciò solleva interrogativi sulla libertà con cui viene dato il consenso e su ciò che i partecipanti comprendono effettivamente di ciò che è accaduto ai dati delle loro riunioni.

Un recente articolo sulle preoccupazioni relative ai sistemi di presa appunti basati sull'intelligenza artificiale spiegava che la semplice presenza di un ascoltatore automatizzato durante una riunione può creare una sensazione di essere osservati o sorvegliati, il che modifica il modo in cui le persone parlano e partecipano. I dipendenti potrebbero ritrovarsi a filtrare il linguaggio, evitare l'incertezza o trattenersi dal contribuire perché sanno che le loro parole vengono registrate e archiviate in modi che vanno ben oltre il momento in cui la conversazione termina.

Questo problema emerge nelle linee guida dei professionisti della privacy e della protezione dei dati che sottolineano come il consenso nell'ambito di quadri normativi quali il GDPR debba essere informato, specifico e significativo. Ad esempio, le organizzazioni devono comunicare ai partecipanti non solo che l'audio verrà registrato, ma anche quali dati vengono acquisiti, dove vengono archiviati, per quanto tempo vengono conservati e chi avrà accesso agli stessi. Dettagli che spesso vengono nascosti negli inviti alle riunioni o nei termini di servizio della piattaforma, anziché essere specificati prima dell'inizio della registrazione.

Registrazione nascosta e strumenti non autorizzati

Uno degli aspetti più fastidiosi emersi riguardo ai dispositivi di registrazione vocale basati sull'intelligenza artificiale è che regole poco chiare e restrizioni generiche non impediscono la registrazione. Cambiano solo il luogo in cui avviene.

Spesso, quando gli strumenti ufficiali risultano limitanti o poco chiari, le persone cercano delle alternative. Cominciano così ad apparire account personali, estensioni per browser, app locali e strumenti progettati per evitare il rilevamento. Una discussione sulla sicurezza informatica sulla cosiddetta"shadow AI"ha descritto un'organizzazione che ha scoperto centinaia di account di note-taker AI non autorizzati che operavano senza approvazione, visibilità o supervisione. Questo comportamento non è sorprendente. I dipendenti spesso scaricano un programma di presa appunti pochi minuti prima di una chiamata importante o attivano funzionalità già esistenti all'interno degli strumenti che utilizzano quotidianamente, come Google Gemini Microsoft 365. La registrazione non sembra una decisione separata quando è integrata in un software familiare e presentata come una comodità predefinita piuttosto che una scelta politica.

Il risultato è un rischio frammentato. Le registrazioni finiscono per essere sparse su account personali, archivi non gestiti e sistemi di cui nessuno nell'IT o nella sicurezza ha visibilità. Le regole di conservazione sono incoerenti. L'accesso non è chiaro. Il riutilizzo dei dati diventa impossibile da tracciare.

Questo è il motivo per cui i divieti generali tendono a sortire l'effetto contrario. Quando la registrazione viene trattata come qualcosa da sopprimere anziché da regolamentare, non scompare. Diventa solo più difficile da vedere. L'uso non ufficiale crea maggiore esposizione rispetto agli strumenti adottati apertamente, spiegati chiaramente e compresi da chi li utilizza.

La registrazione nascosta non è un errore di valutazione da parte dei dipendenti. È un segnale che il divario tra la politica aziendale e la realtà quotidiana è diventato troppo ampio.

Perché queste preoccupazioni meritano attenzione

Nel loro insieme, queste preoccupazioni non sono né irrazionali né ostili nei confronti dell'IA. Riflettono una visione lucida di come i sistemi di presa appunti basati sull'IA alterino il ciclo di vita della comunicazione sul posto di lavoro in modi immediatamente percepibili dalle persone.

Ciò a cui le persone reagiscono è la permanenza, l'attribuzione, la ricercabilità e il riutilizzo, insieme a un cambiamento nel controllo di ciò che accade alle loro parole una volta terminata la riunione. Queste reazioni si collocano all'incrocio tra emozione e conseguenza. Le conversazioni che un tempo svanivano ora persistono. Il contesto viaggia male. La proprietà sembra confusa.

Riconoscere l'importanza della realtà. Senza comprendere come questi strumenti cambino il comportamento e le aspettative, è facile liquidare il disagio come resistenza o affidarsi eccessivamente a rassicurazioni che sembrano sufficienti sulla carta ma che nella pratica si rivelano insufficienti.

Questo contesto è il punto di partenza per qualsiasi valutazione significativa di come i sistemi di presa appunti basati sull'intelligenza artificiale gestiscono la privacy.

La normativa sulla privacy relativa agli assistenti di scrittura vocale basati sull'intelligenza artificiale viene spesso ridotta a una semplice formalità. Alcuni team la considerano una questione che può essere risolta con un semplice clic su una casella. Altri la vedono come un argomento da evitare, a meno che non sia coinvolto l'ufficio legale. Nessuno dei due approcci riflette il modo in cui queste regole si applicano una volta che la registrazione diventa parte integrante del lavoro quotidiano.

Quadri normativi come il GDPR sono importanti in questo contesto perché i sistemi di presa appunti basati sull'intelligenza artificiale trattano conversazioni verbali. Le persone parlano in modo diverso da come scrivono. Si correggono a metà frase. Condividono contesti che potrebbero non inserire mai in un documento. La regolamentazione diventa rilevante proprio perché questi momenti vengono catturati e conservati.

Domande da considerare quando si valutano i dispositivi di presa appunti basati sull'intelligenza artificiale

Ci sono molte ragioni per cui è necessario svolgere alcune verifiche prima di scegliere il giusto sistema di presa appunti basato sull'intelligenza artificiale per le proprie attività aziendali. Ecco alcuni punti da considerare quando si effettua questa scelta.

1) Base giuridica, consenso e interesse legittimo

Una delle prime domande che i team si pongono è se tutti i partecipanti alla riunione debbano acconsentire alla registrazione. La risposta raramente è semplice, ed è proprio qui che spesso nasce il disagio.

Ai sensi del GDPR, le organizzazioni devono disporre di una base giuridica per trattare i dati personali. Il consenso è una delle opzioni possibili. Un'altra è il legittimo interesse. Molti strumenti utilizzati sul posto di lavoro si basano sul legittimo interesse, partendo dal presupposto che il trattamento supporti uno scopo commerciale ragionevole e non prevalga sui diritti individuali.

Gli assistenti di scrittura AI si avvicinano molto a questa ipotesi. La maggior parte delle persone si aspetta che vengano presi appunti. Pochi si aspettano che le loro esatte parole vengano catturate ed elaborate da un sistema automatizzato. Questo divario tra aspettative e realtà è importante, anche quando la base giuridica è tecnicamente valida.

Ecco perché la divulgazione ha così tanta importanza. Quando il consenso non è la base, le persone devono comunque capire cosa succede ai loro dati prima che accada, non dopo che appare una trascrizione.

Se qualcuno partecipasse alla tua riunione aspettandosi appunti anziché una registrazione permanente, penserebbe di aver avuto una vera possibilità di scelta?

2) Riduzione al minimo dei dati in un mondo di trascrizioni complete

La minimizzazione dei dati sembra teorica finché non si scontra con una riunione registrata.

L'idea in sé è semplice. Le organizzazioni dovrebbero raccogliere e conservare solo ciò di cui hanno bisogno. Gli assistenti che utilizzano l'intelligenza artificiale spesso fanno il contrario per impostazione predefinita, acquisendo tutto perché è facile da fare e utile per la ricerca successiva.

Ciò non rende questi strumenti incompatibili con la normativa. Significa semplicemente che i team devono decidere di cosa hanno effettivamente bisogno. Le registrazioni complete potrebbero essere utili. Potrebbero anche essere superflue. Le trascrizioni potrebbero essere preziose per un certo periodo. Potrebbero non essere necessarie per sempre.

La minimizzazione in questo caso riguarda l'intenzione. Qual è il problema che si intende risolvere e quanti dati vengono conservati per risolverlo?

Se un riassunto è sufficiente, perché conservare l'intera conversazione?

3) Diritti di accesso, cancellazione e controllo

La normativa smette di sembrare astratta quando qualcuno chiede di vedere i propri dati.

Ai sensi del GDPR, le persone hanno il diritto di accedere ai propri dati personali e, in molti casi, di richiederne la cancellazione. Quando le riunioni vengono registrate e trascritte, tali diritti si estendono sia ai contributi verbali che a quelli scritti.

Ciò comporta esigenze operative concrete. I team devono sapere dove si trovano le registrazioni (preferibilmente in un unico spazio unificato) e come agire in caso di richieste senza dover ricorrere a supposizioni. È qui che gli strumenti diventano importanti. Le impostazioni di conservazione e i processi di eliminazione smettono di essere un optional e diventano una necessità.

Senza questi controlli, anche i team ben intenzionati possono trovarsi in difficoltà.

Se qualcuno ti chiedesse di rimuovere i propri contributi dalle riunioni passate, potresti farlo in modo pulito?

4) Limitazione delle finalità e uso secondario

La limitazione delle finalità riguarda i confini.

Ai sensi del GDPR, i dati personali devono essere raccolti per uno scopo specifico ed esplicito. Non possono essere successivamente utilizzati per nuovi scopi senza una chiara giustificazione e trasparenza.

Con gli strumenti di presa appunti basati sull'intelligenza artificiale, lo scopo dichiarato è solitamente molto chiaro: registrare la riunione, generare appunti e rendere le informazioni più facili da recuperare.

La domanda più difficile è cosa succederà dopo.

La registrazione rimane limitata a tale scopo o inizia a servire anche ad altri fini? Viene analizzata per ottenere informazioni sulle prestazioni? Viene inserita nei sistemi di analisi? Viene utilizzata per addestrare modelli? Viene condivisa su strumenti interni più ampi?

Queste estensioni non sono automaticamente illegali. Tuttavia, richiedono chiarezza. Se lo scopo originale era quello di prendere appunti, qualsiasi uso più ampio deve essere definito e comunicato fin dall'inizio.

È qui che la fiducia può venir meno. Le persone possono accettare la registrazione a fini di documentazione. Potrebbero però cambiare idea se gli stessi dati vengono utilizzati per analisi o sviluppi di modelli non correlati.

La limitazione delle finalità impone una disciplina semplice. Perché è stato raccolto e viene ancora utilizzato per quello scopo?

Se l'ambito è stato ampliato, è stato chiarito?

Se i dati avessero superato le aspettative dei partecipanti, tale sorpresa sarebbe stata accettabile?

Perché i team incentrati sull'UE sono cauti per natura

Le autorità di regolamentazione europee hanno assunto una posizione ferma in materia di monitoraggio sul posto di lavoro e squilibrio di potere. I dispositivi di registrazione vocale basati sull'intelligenza artificiale toccano entrambi questi ambiti, il che spiega perché i team con sede nell'UE agiscano spesso con cautela.

Questa cautela si manifesta solitamente nelle prime fasi. I team pensano alla conservazione dei dati prima del lancio. Chiedono informazioni sull'accesso prima di abilitare la registrazione. Cercano una giustificazione piuttosto che adeguare le regole in un secondo momento.

Questo è un tentativo di evitare problemi difficili da risolvere una volta persa la fiducia.

Come valutare in modo responsabile un assistente di scrittura basato sull'intelligenza artificiale

Una volta che i team accettano che gli strumenti di presa appunti basati sull'intelligenza artificiale sollevano questioni concrete relative alla privacy e alla sicurezza, la sfida successiva consiste nel sceglierne uno con attenzione. È qui che molte valutazioni si arenano, non perché le persone siano disinteressate, ma perché diventa difficile capire come si comporta uno strumento una volta che supera la fase di demo ed entra nell'uso quotidiano.

Una valutazione responsabile si concentra sui risultati piuttosto che sulle garanzie. L'obiettivo è comprendere cosa succede ai dati relativi agli incontri nel corso del tempo, in situazioni diverse e quando si verificano casi limite.

1) Inizia con domande che descrivono il comportamento

Le prime valutazioni spesso si concentrano sulla conformità di uno strumento ai requisiti normativi. Questo aspetto è importante, ma raramente racconta tutta la storia. È più utile comprendere come funziona il sistema per impostazione predefinita.

- Dove vengono archiviati i dati delle riunioni, comprese le regioni coinvolte

- Per quanto tempo vengono conservate le registrazioni e le trascrizioni prima della loro rimozione?

- Chi può visualizzare registrazioni, trascrizioni o sintesi dopo una riunione

- Se l'accesso cambia in base al ruolo, all'area di lavoro o alla proprietà

- Cosa succede ai dati quando qualcuno lascia l'organizzazione

Gli strumenti che gestiscono bene questi aspetti rendono più facile per i team spiegare l'utilizzo internamente e applicare regole coerenti senza attriti.

2) Consenso, divulgazione e aspettative

La registrazione funziona meglio quando le persone capiscono cosa sta succedendo prima che inizi. La valutazione dovrebbe esaminare attentamente il modo in cui gli strumenti comunicano lo stato della registrazione durante le riunioni reali.

- Notifica chiara all'avvio della registrazione

- Possibilità di attivare o disattivare la registrazione per ogni riunione

- Gestione prevedibile dei ritardatari

- Segnali visibili per partecipanti esterni, come un bot

Quando la registrazione è esplicita e deliberata, i team si sentono più a loro agio nell'utilizzarla e sono meno propensi a creare soluzioni alternative.

3) Elaborazione AI e utilizzo del modello

Il modo in cui i sistemi di IA interagiscono con i dati delle riunioni è un aspetto fondamentale da considerare durante la valutazione.

- Se i dati delle riunioni contribuiscono alla formazione del modello

- Se l'elaborazione è isolata per cliente

- Quali dati rimangono dopo la generazione dei riepiloghi

- Se sono coinvolti modelli di terze parti

Gli strumenti che spiegano chiaramente questi flussi e sono progettati per garantire l'isolamento danno ai team la certezza che i loro dati saranno gestiti in modo sicuro anche al di là della riunione immediata.

4) Elaborazione AI e utilizzo del modello

Il modo in cui i sistemi di IA interagiscono con i dati delle riunioni è un aspetto fondamentale da considerare durante la valutazione.

- Se i dati delle riunioni contribuiscono alla formazione del modello

- Se l'elaborazione è isolata per cliente

- Quali dati rimangono dopo la generazione dei riepiloghi

- Se sono coinvolti modelli di terze parti

Gli strumenti che spiegano chiaramente questi flussi e sono progettati per garantire l'isolamento danno ai team la certezza che i loro dati saranno gestiti in modo sicuro anche al di là della riunione immediata.

5) Riconoscere le risposte incomplete

Durante le valutazioni, alcune risposte segnalano la necessità di una discussione più approfondita.

- Affermazioni generiche di conformità senza spiegazioni

- Riferimenti a certificazioni non legate ai flussi di lavoro di registrazione

- Dichiarazioni sulla sicurezza senza dettagli sull'accesso o la conservazione

- Forte dipendenza dalle politiche senza controlli di sistema di supporto

Le valutazioni più severe considerano questi aspetti come spunti di chiarimento piuttosto che come segnali di allarme.

6) Valutazione dell'impatto all'interno dell'organizzazione

Una valutazione responsabile include anche una riflessione sull'uso interno.

- Come la registrazione si inserisce nella cultura delle riunioni esistente

- Chi decide quando è opportuno registrare

- Quali indicazioni ricevono le persone prima di utilizzare lo strumento

- Come vengono gestite le preoccupazioni o le rinunce

Quando queste decisioni vengono prese tempestivamente, i team sono più propensi a utilizzare lo strumento apertamente piuttosto che evitarlo silenziosamente.

Le risposte più convincenti tendono a includere

Le risposte più utili si concentrano sul comportamento del prodotto in condizioni di utilizzo normale piuttosto che su casi limite.

- Chiaro spiegazione delle impostazioni predefinite

- Descrizione chiara dell'accesso in scenari quotidiani

- Riconoscimento onesto dei limiti o dei vincoli

- Documentazione che riflette l'effettivo utilizzo dello strumento

Questo tipo di dettagli rende più facile per i team implementare gli strumenti in modo responsabile e fornirne assistenza nel tempo.

Alla ricerca di prove al di là della conversazione

La valutazione è più efficace quando va oltre le conversazioni di vendita e si concentra su prove che esistono indipendentemente da esse.

I centri di sicurezza o di fiducia accessibili al pubblico e costantemente aggiornati, la documentazione che spiega chiaramente come funzionano nella pratica la registrazione e la trascrizione e le descrizioni trasparenti di come i dati si muovono tra i sistemi fanno la differenza. Le verifiche indipendenti che riflettono l'utilizzo reale piuttosto che la conformità astratta aggiungono ulteriore peso. La disponibilità di questo materiale rende più facile per i team di sicurezza, legali e operativi allinearsi tempestivamente e supportare un'implementazione responsabile nel tempo.

Come i fornitori responsabili mitigano i rischi per la privacy nella pratica

I fornitori responsabili mitigano i rischi per la privacy attraverso decisioni concrete sui prodotti piuttosto che generiche garanzie. Queste decisioni si riflettono nel funzionamento della registrazione, nell'accesso ai contenuti, nella durata dei dati e nella gestione dell'elaborazione AI dietro le quinte.

Una delle aree più visibili è la registrazione stessa. Gli strumenti responsabili rendono la registrazione esplicita anziché nascosta. Nel caso tl;dv, le riunioni vengono registrate tramite un bot visibile che si unisce alla chiamata, rendendo la registrazione evidente a tutti i partecipanti. Gli host possono avviare o interrompere la registrazione, che non è progettata per essere eseguita silenziosamente in background. Ciò riduce il rischio di sorprese e favorisce una partecipazione consapevole fin dall'inizio.

L'accesso ai contenuti registrati è un altro ambito in cui l'implementazione è importante. tl;dv l'accesso alle registrazioni e alle trascrizioni a livello di spazio di lavoro, anziché rendere i contenuti visibili a tutti per impostazione predefinita. Ciò significa che le registrazioni sono disponibili solo alle persone all'interno dello spazio di lavoro pertinente e che la condivisione al di fuori di tale contesto è controllata. Questo approccio limita la diffusione involontaria e allinea l'accesso al contesto originale della riunione.

La conservazione e la cancellazione sono trattate come controlli operativi piuttosto che come casi limite. tl;dv ai team di gestire la durata di conservazione delle registrazioni e delle trascrizioni, mentre la cancellazione rimuove i dati sottostanti della riunione anziché limitarne semplicemente la visualizzazione. I riassunti e i risultati generati dall'intelligenza artificiale seguono lo stesso ciclo di vita del materiale di origine, il che consente una gestione prevedibile nel tempo.

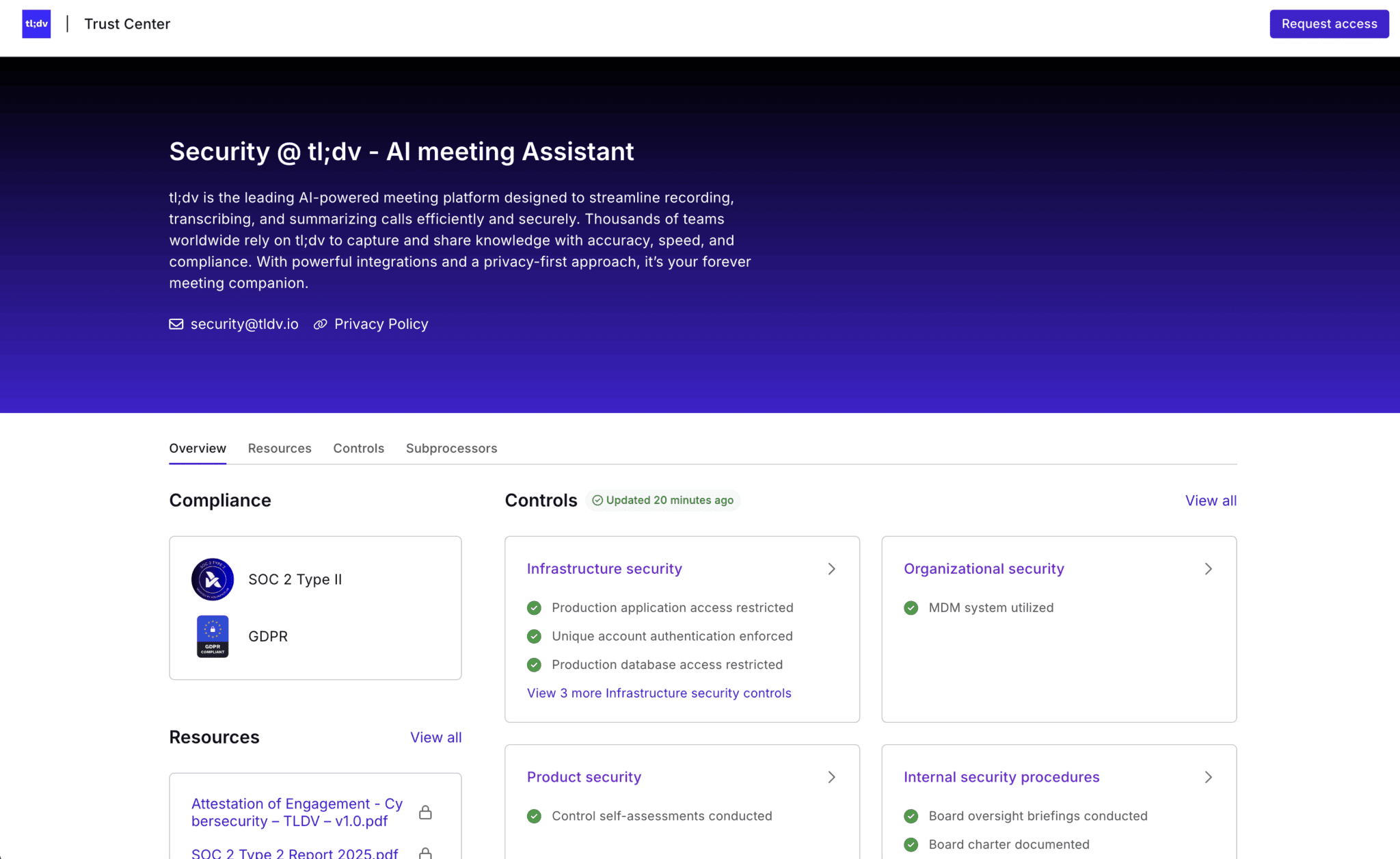

I limiti dell'elaborazione dell'IA sono documentati in modo esplicito nel Centro di fiducia tl;dv.

Secondo i materiali pubblicati, i dati delle riunioni con i clienti vengono elaborati esclusivamente per fornire funzionalità quali trascrizioni, sintesi e approfondimenti, e non vengono utilizzati per addestrare modelli di IA più ampi, una distinzione che aiuta i team a valutare il rischio di un uso secondario perché traccia una linea chiara su come i dati vengono gestiti al di là della riunione immediata. Il Trust Center include anche artefatti indipendenti come un'attestazione SOC 2 Tipo II e un rapporto sui test di penetrazione, insieme a dettagli sull'infrastruttura e sui controlli organizzativi, che mostrano come l'accesso e l'elaborazione sono regolati nelle operazioni quotidiane.

Il luogo in cui risiedono queste informazioni è importante quanto il contenuto stesso. tl;dv gli impegni a livello di sistema dal comportamento quotidiano. Il suo Trust Centre documenta la sicurezza, la gestione dei dati e le pratiche di elaborazione ad alto livello, mentre il suo Help Centre spiega come funziona la registrazione, come viene gestito l'accesso e come possono essere applicate nella pratica le impostazioni di conservazione. Ciò rende più facile per i team valutare la piattaforma durante l'approvvigionamento e comprenderne il comportamento una volta che è in uso.

Nessuna di queste misure elimina completamente il rischio. Riducono l'ambiguità. Limitano l'esposizione accidentale. Supportano un uso consapevole senza ricorrere a soluzioni alternative informali.

Quando i fornitori documentano il funzionamento dei propri sistemi, progettano la visibilità e garantiscono ai team il controllo sull'accesso e la conservazione dei dati, la privacy diventa parte integrante del funzionamento del prodotto anziché un elemento aggiunto a posteriori. Questo è ciò che significa mitigazione responsabile nella pratica.

Scegliere un assistente di scrittura AI senza rischiare la fiducia

Gli assistenti di scrittura AI si trovano in una posizione scomoda. Promettono di alleggerire il carico amministrativo, migliorare la memoria e ridurre il numero di dettagli tralasciati, ma allo stesso tempo toccano la parte più umana del lavoro, ovvero la conversazione. È comprensibile che le persone esitino prima di consentire a questi strumenti di ascoltare, ricordare e riassumere ciò che dicono sul lavoro.

Questa esitazione riflette la consapevolezza istintiva che, una volta registrate ed elaborate le conversazioni, la situazione cambia. Le parole durano più a lungo. Il contesto va oltre l'intenzione iniziale. Ciò che sembrava informale può improvvisamente diventare permanente. Il controllo inizia ad avere un'importanza che prima non aveva.

Scegliere in modo responsabile non significa rinunciare a questi strumenti. Significa prestare attenzione al loro comportamento predefinito, alla chiarezza con cui si spiegano e alla loro adeguatezza alla realtà complessa delle riunioni reali piuttosto che a quelle idealizzate. La visibilità batte sempre l'invisibilità. Le impostazioni predefinite contano più dei casi limite. Una documentazione chiara conta più delle rassicurazioni in una chiamata di vendita.

Aiuta anche a separare il provare qualcosa dall'impegnarsi a farlo. Molti team traggono vantaggio dall'utilizzo di questi strumenti in contesti a basso rischio, verificando come funzionano effettivamente la registrazione, l'accesso e la conservazione dei dati e decidendo cosa è accettabile prima di implementarli su più ampia scala. Questo tipo di approccio rispetta sia l'efficienza che le persone le cui conversazioni vengono registrate.

Quando i team vogliono approfondire, il segnale più forte raramente è una demo o una conversazione con un abile rappresentante commerciale. È piuttosto la documentazione scritta che un fornitore lascia. I centri di fiducia, le pagine sulla sicurezza e gli articoli di assistenza mostrano come viene gestita la privacy quando nessuno sta cercando di convincerti. Rendono più facile capire cosa viene registrato, chi può vederlo, per quanto tempo rimane disponibile e dove si ferma l'elaborazione dell'IA.

Fornitori come tl;dv pubblicano apertamente questo materiale, tracciando una linea netta tra gli impegni di alto livello e i dettagli pratici dell'uso quotidiano. Ciò offre ai team lo spazio necessario per verificare autonomamente le affermazioni, anziché accettarle ciecamente.

Adottare strumenti di presa appunti basati sull'intelligenza artificiale non dovrebbe essere un atto di fede. Con le domande giuste, una documentazione chiara e la volontà di procedere con cautela, i team possono utilizzare questi strumenti senza minare silenziosamente la fiducia che rende efficaci le riunioni.

Domande frequenti sull'intelligenza artificiale e la privacy

A partire dal 2026, i sistemi di presa appunti basati sull'intelligenza artificiale saranno legali ai sensi del GDPR?

È possibile, ma solo quando esiste una chiara base giuridica per il trattamento, un'adeguata informativa prima della registrazione e controlli in atto per l'accesso, la conservazione e la cancellazione. La semplice notifica ai partecipanti dopo il fatto non è sufficiente.

I sistemi di presa appunti basati sull'intelligenza artificiale utilizzano i dati delle riunioni per addestrare i propri modelli?

Dipende dal fornitore. Alcuni strumenti dichiarano che i dati dei clienti non vengono utilizzati per l'addestramento dei modelli, mentre altri possono fare affidamento su accordi di elaborazione più ampi. Controlla sempre attentamente la documentazione piuttosto che affidarti alle dichiarazioni di marketing.

Gli assistenti di scrittura AI dovrebbero essere utilizzati nelle riunioni delle risorse umane, legali o finanziarie?

Questi contesti richiedono una maggiore sensibilità perché le conversazioni spesso riguardano informazioni riservate o di grande impatto. Molti team limitano o evitano la registrazione in questi contesti, a meno che non vi sia una necessità chiara e documentata e non siano in atto rigorosi controlli sui dati.

Cosa dovremmo verificare prima di scegliere un sistema di presa appunti basato sull'intelligenza artificiale?

Verificate dove vengono archiviati i dati, per quanto tempo vengono conservati, chi può accedervi per impostazione predefinita, se la cancellazione rimuove completamente le registrazioni e le trascrizioni, come funziona l'elaborazione AI e se il fornitore offre una documentazione trasparente in materia di sicurezza e affidabilità che rifletta l'uso reale.